根据以太坊官方网站的说法,“最大可提取价值”(MEV)是一个功能而不是一个错误。 MEV 是由于矿工,或者更确切地说,在几乎所有情况下,矿池决定了哪些交易,来自未决交易的公共内存池,或来自暗池,或来自矿池本身,将被包含在他们开采的区块中,以及以什么顺序。该顺序在以太坊等图灵完备的区块链中尤为重要;允许矿工从其他地方抢先运行、反向运行或夹层交易。这样做的利润是 MEV。 MEV 正从矿工可提取价值重命名为最大可提取价值,因为事实证明,矿工并不是唯一可以提取它的参与者。

| |

| 以太坊挖矿 11/07/21 |

在以太坊中,MEV 的利润得到了提升,因为挖矿是由极少数的大型矿池主导的;去年 11 月,两个矿池共享了大部分采矿权。因此,这些矿池很有可能会挖掘下一个区块,从而获得 MEV。请注意, 在传统金融中,抢先交易等活动是非法的,尽管高频交易者可以说使用这些技术。

我在Ethereum Has Issues中写了关于这些问题的文章,讨论了 Philip Daian 等人的Flash Boys 2.0:去中心化交易所中的领先优势、矿工可提取价值和共识不稳定性和 Julien Piet等人从盐矿中提取 Godl [原文如此]:以太坊矿工提取 Value ,但这只是表面上。在首屏下方,我回顾了另外十个贡献。

Eskandari等人(2019 年 4 月 9日)

Sok:透明的不诚实行为:S. Eskandari、S. Moosavi 和 J. Clark 对区块链的抢先攻击是对以太坊抢先行为的早期调查。从他们的摘要中:

我们认为抢先交易是一种行为方式,在这种行为中,实体可以从事先获得有关即将进行的交易和交易的特权市场信息中受益。自 1970 年代以来,抢先交易一直是金融工具市场的一个问题。随着区块链技术的出现,在区块链的去中心化和透明性的推动下,抢先交易以我们在这里探索的新形式重新出现。在本文中,我们从分散的知识体系和部署在以太坊区块链上的前 25 个最活跃的去中心化应用程序 (DApp) 的前沿实例中得出结论。此外,我们对Status.im初始代币发行 (ICO) 进行了详细分析,并显示矿工异常行为的证据表明抢先购买代币。最后,我们将建议的解决方案映射到前端运行到有用的类别中。

他们这样定义了以太坊的前端漏洞:

任何监视网络事务的用户(例如,运行一个完整节点)都可以看到未确认的事务。在以太坊区块链上,用户必须以称为气体的少量以太币支付计算费用。用户为交易支付的价格 gasPrice 可以增加或减少矿工执行交易的速度,并将其包含在他们开采的区块中。一个以利润为动机的矿工看到相同的交易具有不同的交易费用,将优先考虑由于区块空间有限而支付更高gas价格的交易。 …因此,任何运行全节点以太坊客户端的普通用户都可以通过发送具有更高 gas 价格的自适应交易来提前处理待处理交易

他们将抢先攻击分为三类:

位移、插入和压制攻击。在所有这三种情况下,Alice 都试图在处于特定状态的合约上调用一个函数,而 Mallory 将尝试在 Alice 之前对处于相同状态的同一个合约调用她自己的函数调用。

在第一种攻击类型中,位移攻击,对于对手来说,在 Mallory 运行她的函数之后运行 Alice 的函数调用并不重要。爱丽丝可以成为孤儿或运行而没有任何有意义的影响。置换的例子包括: Alice 尝试注册一个域名,而 Mallory 先注册了它; Alice 试图提交一个 bug 以获得赏金,而 Mallory 偷了它并首先提交;爱丽丝试图在拍卖中提交出价,而马洛里复制了它。

在插入攻击中,在 Mallory 运行她的函数后,合约的状态发生了变化,她需要 Alice 的原始函数在这个修改后的状态上运行。例如,如果 Alice 以高于最优报价的价格购买区块链资产,Mallory 将插入两个交易:她将以最优报价购买,然后以 Alice 略高的购买价格出售相同的资产.如果 Alice 的交易随后运行,Mallory 将在价格差异中获利,而无需持有资产。

在一次抑制攻击中,Mallory 运行她的函数后,她试图延迟 Alice 运行她的函数。延迟之后,她对 Alice 的函数是否运行无动于衷。

他们检查了一系列以太坊 DApp。也许最能说明问题的是他们对Status.im ICO 的研究。像往常一样,在需求旺盛的时候,以太坊网络遭受了严重的拥塞:

在 ICO 开放参与的时间范围内,有报道称以太坊网络无法使用且交易未确认。 … 有许多交易以更高的 gas 价格发送以抢占其他交易,但是,由于 ICO 智能合约中限制拒绝高于 50 GWei gas 价格的交易(作为缓解领先)。

|

| Eskandari等人图 3 |

而且,像往常一样,以太坊挖矿由几个大型矿池主导;在这种情况下,Ethermine 和 F2Pool 控制了 49% 的挖矿算力。 Eskandari等人发现其中至少有一个正在通过抢先交易滥用系统:

F2Pool——一个以太坊矿池,当时拥有大约 23% 的挖矿哈希率——在Status.im ICO 开始之前向 30 个新的以太坊地址发送了 100 个以太币。当 ICO 开放时,F2Pool 从他们的地址向 ICO 智能合约构建了 31 笔交易,而没有将交易广播到网络。他们利用自己的全部挖矿能力来挖掘自己的交易和其他一些可能失败的高油价交易。

添加了“高gas价格交易”以使网络拥塞并减少竞争交易被确认的机会。 Eskandari等人从 30 个地址中追踪了以太币,发现:

F2Pool 在这些地址中存入的资金被发送到Status.im ICO 并由 F2Pool 自己开采,其中动态上限算法退还了一部分存入的资金。在这些资金被送回 F2Pool 主地址几天后,这些代币随后被汇总到一个地址中。

这个早期的例子清楚地展示了一个矿池使用他们插入非公开交易来生成 MEV 的能力。

Zhou等人(2020 年 9 月 29日)

L. Zhou、K. Qin、CF Torres、DV Le 和 A. Gervais在去中心化链上交易所的高频交易中:

专注于单个链上 DEX 的前后运行组合,称为三明治。据我们所知,我们是第一个将三明治攻击形式化和量化的人。

他们强调:

虽然 SEC 将抢先交易定义为针对私人信息的行动,但我们只针对公共贸易信息进行操作。

他们声称有四个贡献:

- 三明治攻击的形式化。我们陈述了 AMM [自动做市商] 机制和三明治攻击的数学形式,为攻击者提供了一个框架来管理他们的资产组合并最大化攻击的盈利能力。

- 分析和实证评价。我们通过分析和经验评估对 AMM DEX 的三明治攻击。除了对抗性流动性接受者之外,我们还引入了由对抗性流动性提供者执行的一类新的三明治攻击。我们量化了最佳对抗性收入,并在 Uniswap 交易所(最大的 DEX,在撰写本文时交易量为 500 万美元)上验证了我们的结果。我们的实证结果表明,一个对手可以实现 3,414 美元的平均每日收入。即使没有与矿工勾结,我们发现,在没有其他对手的情况下,使用 ±1 Wei 的交易费用支付策略,在区块链区块内的另一笔交易之前或之后定位交易的可能性至少为 79%。

- 多人攻击游戏。我们在遵循反应性反投标策略的多个同时攻击者下模拟三明治攻击。我们发现,假设有交易的受害者,2、5 和 10 名攻击者的存在分别使每个攻击者的预期盈利能力降低 51.0%、81.4% 和 91.5%,分别为 0.45、0.17、0.08 ETH(67、25、12 美元) Uniswap 上的 20 ETH 到 DAI,交易在 P2P 层待处理 10 秒,然后被挖掘。如果区块链拥塞(即受害者交易保持未决的时间超过平均区块间隔),我们表明攻击者的盈亏平衡变得更难实现。

- DEX 安全性与可扩展性的权衡。我们的工作揭示了 AMM DEX 的安全性和可扩展性之间的内在张力。如果 DEX 使用安全(即在低或零价格滑点下),在高交易量下交易可能会失败;否则,对抗性交易者可能会获利。

这里有很多有趣的点。令人吃惊的是,即使是 1 Wei 的小差异,也几乎有五分之四的机会正确定位。这意味着即使没有矿工,一个单独的三明治交易商也可以每年赚取大约 125 万美元。但是,当然,这样的机会很快就会被抢走,尤其是当受害者交易在多个区块中可见时。暗池的优势显而易见。

他们确定的权衡很有趣,因为它是基于不可避免的“价格滑点”:

价格滑点是交易期间资产价格的变化。预期价格滑点是基于交易量和可用流动性的预期价格上涨或下跌,预期在交易开始时形成。交易量越高,预期滑点就越大……意外价格滑点是指在提交交易承诺后的中间期间,价格在预期滑点之上的任何额外增加或减少到它的执行。

他们这样描述权衡:

我们的工作揭示了 DEX 面临的两难境地:如果默认滑点设置得太低,则 DEX 不可扩展(即每个区块只支持很少的交易),如果默认滑点太高,对手可以获利。

Zhou等人(2021 年3月 3 日)

在Defi 协议中即时发现盈利交易中,Liyi Zhou、Kaihua Qin、Antoine Cully、Benjamin Livshits 和 Arthur Gervais:

研究两种允许我们自动创建有利可图的 DeFi 交易的方法,一种非常适合套利,另一种适用于更复杂的设置。我们首先采用带 DEFIPOSERARB 的 Bellman-Ford-Moore 算法,然后在 DEFIPOSER-SMT 中为定理证明器创建逻辑 DeFi 协议模型。虽然 DEFIPOSER-ARB 专注于形成循环并在套利方面表现非常出色的 DeFi 交易,但 DEFIPOSER-SMT 可以检测更复杂的盈利交易。我们估计 DEFIPOSER-ARB 和 DEFIPOSER-SMT 可以分别产生 191.48 ETH(76,592 美元)和 72.44 ETH(28,976 美元)的平均每周收入,最高交易收入分别为 81.31 ETH(32,524 美元)和 22.40 ETH(8,960 美元) ) 分别。

他们分析的关键是在多个 DeFi 平台上执行交易的能力:

DeFi 平台的一个特点是它们的互操作能力。例如,一个人可以在一个平台上借入一种加密货币资产,在另一个平台上交换该资产,例如,在第三个系统上借出所得资产。 DeFi 的可组合性导致在紧密交织的 DeFi 空间中出现了链式交易和套利机会。推理这个简单的组合需要什么并不是特别简单。一方面,原子组合允许执行无风险套利——即在不同的 DeFi 市场上使资产价格相等。套利是保持市场同步的良性且重要的努力。

另一方面,我们已经看到了数百万收入的交易,它们巧妙地利用闪电贷款的技术来利用 DeFi 协议中的经济状态……然而,虽然利用经济状态并不是传统意义上的安全攻击,但从业者社区经常将这些高收入交易视为“黑客”。然而,执行交易者遵循已部署的智能合约规定的规则。无论框架如何,参与 DeFi 的流动性提供者都会遭受数百万美元的意外损失。

他们通过展示以下内容来验证他们的方法:

DEFIPOSER-SMT 从 2020 年 2 月开始发现已知的经济 bZx 攻击,产生 48 万美元。我们的法医调查表明,这个机会存在了 69 天,如果提前一天利用,可能会产生更多收入。

DEFIPOSER-SMT 发现的攻击细节如下:

2020 年 2 月 15 日,交易员对保证金交易平台 bZx3 进行了拉高和套利攻击。这笔交易的核心是一次交易中原子执行的四个 DeFi 平台的抽水和套利。 … 这笔交易导致 bZx 贷款提供商损失 4,337.62 ETH(1,735,048 美元),交易者总共获得 1,193.69 ETH(477,476 美元)

|

| Zhou等人图 7 |

他们的结果的一个有趣方面是使用的资本与回报之间的关系:

我们在图 7 中将 DEFIPOSER-SMT 和 DEFIPOSER-ARB 产生的收入可视化为初始资本的函数。如果交易者拥有基础资产(例如 ETH),大多数策略需要少于 150 ETH。 DEFIPOSER-SMT 只有 10 个策略需要超过 100 ETH,而 DEFIPOSER-ARB 只有 7 个策略需要超过 150 ETH。

但是可以避免这种对资金的需求:

使用闪贷时,该资本要求降至 1.00 ETH(400 美元)以下(参见图 7 (b, d))。

Eric Budish 表明,为了安全起见,比特币区块中的交易价值不得超过区块奖励。 Zhou等人研究了他们发现的 MEV 对以太坊安全性的影响:

除了上述财务收益之外,分叉还会恶化区块链共识的安全性,因为它们增加了双花和自私挖矿的风险。我们探讨了 DEFIPOSER-ARB 和 DEFIPOSER-SMT 对区块链共识的影响。具体来说,我们展示了我们的工具识别的交易超过以太坊区块奖励高达 874 倍。鉴于马尔可夫决策过程 (MDP) 提供的最佳对抗策略,我们量化了盈利交易符合矿工可提取价值 (MEV) 的价值阈值,并将激励具有 MEV 意识的矿工分叉区块链。例如,我们发现在以太坊上,如果 MEV 机会超过区块奖励的 4 倍,哈希率为 10% 的矿工将分叉区块链。

| |

| ETH 挖矿 09/03/22 |

请注意,正如我所写,三个矿池的 ETH 哈希率超过 10%(Ethermine 27.1、f2pool 15.5、Hiveon.net 10.2),总计 52.8%。因此,Zhou等人确定的以太坊安全风险是非常真实的。

Torres等人(2021 年 8 月 11日)

领跑者琼斯和黑暗森林的袭击者:Christof Ferreira Torres、Ramiro Camino 和 Radu State 对以太坊区块链上的领跑者的实证研究:

旨在揭示所谓的黑暗森林并揭示这些掠食者的行为。我们提出了一种有效测量三种类型的抢先运行的方法:位移、插入和抑制。我们对超过 1100 万个区块进行了大规模分析,并确定了近 20 万次攻击,攻击者累计获利 1841 万美元,这证明抢先交易既有利可图,又是一个普遍存在的问题。

平均每次攻击约 9,200 美元。考虑到偏态分布,这非常小。作者在图 7 中提供了攻击成本和利润的细分。最可能的结果是:

- 排量:成本约 10 美元,利润超过 100 美元。

- 插入:成本低于 10 美元,利润低于 100 美元。

- 抑制:成本约 1,000 美元,利润约 10,000 美元。

因此,典型的投资回报率约为 10 倍。尽管每次攻击的美元利润相对较小,但自动化和 10 倍的投资回报率足以激励攻击者。

Torres等人观察到与Zhou等人相同的 DEX 困境:

Uniswap 是受抢先交易影响最大的 DEX,它意识到了抢先交易的问题,并提出了一个滑点容限参数,该参数定义了交易价格在执行前后的距离。容忍度越高,交易越有可能通过,但攻击者越容易抢先交易。容忍度越低,交易越有可能无法通过,但攻击者越难以抢先交易。结果,Uniswap 的用户陷入了两难境地。

Judmayer等人(2021 年 9 月 21日)

估计(矿工)可提取价值很难,我们去购物吧! Aljosha Judmayer、Nicholas Stifter、Philipp Schindler 和 Edgar Weippl 描述:

不同形式的可提取价值以及它们如何相互关联。此外,我们概述了一系列观察结果,这些观察结果强调了定义这些不同形式的可提取价值的困难,以及为什么在不假设所有可用资源(例如,其他加密货币)是或可能与经济理性的参与者相关的。我们还描述了一种估计最小可提取价值的方法,以参考资源的标准化块奖励的倍数来衡量,以激励可能导致共识不稳定的参与者的对抗行为。最后,我们提出了一种独特而直接的技术来选择个人安全参数 k,而不考虑可提取的价值机会。

他们解释了k的作用:

由于 MEV/BEV 的概念与是否分叉某个区块/链 [ 44 ] 的经济激励相关,因此这个问题也与关于商户个人安全参数 k 选择的经济考虑有关。对总体 MEV/BEV 值的准确估计将允许在总体 MEV/BEV 较高的时期内相应地调整和增加 k。安全参数 k 的选择,它决定了在可以安全地认为支付被确认之前所需的确认块的数量,已经在各种工作中进行了研究。 Rosenfeld [ 35 ] 表明,虽然等待更多的确认会以指数方式降低攻击成功的概率,但在 PoW 的概率安全模型中,没有任何确认量会将攻击的成功率降低到 0,并且经常- 引用的 k = 6 个确认的数字。

Goharshady表明,商家在为加密货币出售商品(甚至法定货币)时存在不可避免的风险。在第 4.1 节中,作者描述了一种技术,商家可以通过该技术选择 k 以便将这种风险转移给他们的交易对手。

注意:我找不到这篇论文的具体发表日期,2021 年 9 月 21日的日期来自Wayback Machine 。

Obadia等人(2021 年 12 月 7日)

团结就是力量:Alexandre Obadia、Alejo Salles、Lakshman Sankar、Tarun Chitra、Vaibhav Chellani 和 Philip Daian 对跨领域最大可提取价值的形式化研究了 MEV 跨多个互连区块链的潜力:

在这项工作中,我们将这些相互关联的区块链中的每一个称为“域”,并研究它们之间的最大可提取价值(MEV,“矿工可提取价值”的概括)的表现形式。换句话说,我们调查是否存在依赖于两个或多个域中的交易顺序的可提取价值。

有许多类型的域:

第 1 层、第 2 层、侧链、分片、中心化交易所都是域的示例。

跨域最大可提取价值的关键是:

MEV 提取历来被认为是单个域上的自包含过程,单个参与者(传统上是矿工)赚取作为隐性交易费用的原子利润。在多链的未来,如果需要跨多个域的行动以实现利润最大化,从多个域中提取最大可能价值可能需要每个域的排序器的协作或共谋。

…

我们预计,鉴于在多个领域部署 AMM 和其他载有 MEV 的技术,跨多个领域提取 MEV 的好处通常会超过共谋的成本

|

| 奥巴迪亚图 1 |

因此:

由于它存在于各个领域并且是有限的,因此对此类机会的竞争将非常激烈,并且可能没有任何桥梁能够足够快地执行完整的套利交易,如图 1 所示。

一个观察结果是,已经拥有跨两个领域资产的参与者不需要桥接资金来获取 MEV 利润,从而减少交易所需的时间、复杂性和信任。这意味着可以在两个同时交易中抓住跨域机会,跨多个域的库存管理是玩家优化其 MEV 奖励的策略的内部。

对于权力下放的倡导者来说,这是一个问题,因为:

这种行为类似于传统金融中做市商和桥梁的库存管理实践,主要包括将资产分散在多个异构信任域(通常是中心化交易所),管理与这些域相关的风险,并确定相对定价.一些关键差异包括与系统中的参与者(而不是他们自己)进行协调的能力,例如通过 DAO 或 Flashbots 等系统。然而,鉴于这些结论,传统金融参与者可能在跨领域 MEV 风险管理中具有基于知识的优势,这可能会导致来自这些参与者的中心化向量能够运行更有利可图的验证器。

尽管很严峻,但这一事实很重要,因为它揭示了跨域交互的一个关键属性:可组合性的丧失。不再有原子执行。这带来了额外的执行风险,并且需要更高的资本要求,进一步提高了提取 MEV 所需的准入门槛。

这不是作者指出的唯一“负外部性”。另一个来自大型投币矿工或验证者的主导地位,他们有能力同时在多个领域占据主导地位:

跨域可提取价值可能会激励排序者(即大多数域中的验证者)在具有最大可提取价值的网络中积累选票。

当意识到已经存在跨多个网络运行基础设施的大型验证者和质押提供商时,这一点尤其重要。如果此类收入可观,营利性实体不太可能长期放弃获得 MEV 收入。

另一个是共识不稳定的风险:

Time-bandit 攻击最早是在 [ Daian等人] 中引入的,包括观察矿工有直接经济动机来重组其正在挖掘的链的情况。

在跨域设置中,现在可能存在重组多个域或重组较弱域以执行类似于双花的攻击的动机。这将与桥梁的安全性特别相关。

另一个来自我最喜欢的问题,对等网络中的规模经济:

一个普遍的担忧是潜在的规模经济或护城河,贸易商可以跨领域创造,这最终会增加新进入者的进入壁垒并体现现有参与者的主导地位。

例子。假设域以先进先出 (FIFO) 的方式对事务进行排序。这样的域有效地在追求相同机会的交易者之间产生了延迟竞赛。正如在传统市场中所见,交易者可能会投资延迟基础设施以保持竞争力,这可能会降低市场效率。

如果多个域也有这样的排序规则,交易者可以在每个域中进行延迟竞赛,或者在域之间传播套利的延迟竞赛,从而使这些系统运行的地理点成为延迟套利的目标。为优化一个领域而开发的基础设施很可能可以跨多个领域使用。这可以创造一个“超级”延迟玩家,并且肯定有利于那些已经在传统金融中构建此类系统方面拥有相当专业知识的实体。这种对延迟敏感的系统可能会通过在跨域 MEV 游戏中利用延迟优化的玩家来侵蚀不依赖延迟的系统的安全性。该领域值得进一步研究,因为众所周知,全球网络延迟在 Nakamoto 风格的协议中需要相对较长的阻塞时间才能实现异步下的安全性 [ Pass等人],并且跨域 MEV 可能会侵蚀此类协议中验证者奖励的公平性。

最后,跨域最大可提取价值的结果是:

在区块链生态系统的不同参与者之间引入异构定价模型。以前,MEV 是一个以通用基础资产 ETH 计价的明确数量。在多链的未来,参与者之间的相对价格差异不仅与计算 MEV 有关,实际上还可以创建 MEV。例如,前一个验证者可能会让系统处于其定价模型中的 0-MEV 状态,但不同意这种定价模型的下一个验证者可能会看到重新平衡 MEV 的机会,以增加其主观估值的资产。这为为什么 MEV 是全局、无许可系统的基础提供了另一种直觉,即使它们不受 [ Daian等人] 中描述的那种排序操作的影响。

综上所述,在多个领域执行交易所产生的 MEV 的可用性极大地有利于大型参与者,特别是那些具有传统金融专业知识的参与者,并增加了共识不稳定的风险。

秦等人(2021 年 12 月 10日)

量化区块链可提取价值:森林有多黑? Kaihua Qin、Liyi Zhou 和 Arthur Gervais 提出了三个主要贡献:

- 我们是第一个从已知交易活动(即三明治攻击、清算和套利)中全面衡量 BEV 广度的人。尽管相关工作已经孤立地研究了三明治攻击,但缺乏来自现实世界利用的定量数据来客观地评估其严重性。

- 我们是第一个提出并根据经验评估交易重放算法的人,该算法可能产生 3537 万美元的 BEV。我们的算法将捕获的总 BEV 扩展了 3518 万美元,同时仅与 1.43% 的清算和 0.11% 的套利交易相交

- 我们率先将 BEV 中继概念正式化为 P2P 交易费用拍卖模型的扩展。与从业者社区的建议相反,我们发现 BEV 中继器并没有显着降低竞争交易的 P2P 网络开销。

作者检查了从 2018 年 12 月 1 日到 2021 年 8 月 5 日超过 32 个月的交易,寻找三种类型的攻击。至于三明治攻击,他们发现:

2,419 个以太坊用户地址和 1,069 个智能合约对 Uniswap V1/V2/V3、Sushiswap 和 Bancor 执行 750,529 次三明治攻击,总利润为 1.7434 亿美元(参见图 3)。我们的启发式算法没有发现对 Curve、Swerve 和 1inch 的三明治攻击。 Curve/Swerve 专门用于相关的,即具有最小滑点的挂钩硬币。尽管市值很小。 (

我们注意到,有 240,053 次三明治攻击(31.98%)被私下转发给矿工(即零 gas 价格),累计获利 8104 万美元。因此,三明治攻击者积极利用 BEV 中继系统(参见第 VI-A 节)来提取价值。我们还观察到 17.57% 的攻击使用不同的攻击 我们还观察到 17.57% 的攻击使用不同的帐户来发出前后端运行的交易。

…

周等人。 [2] 估计在最优设置下,攻击者可以攻击 7,793 笔 Uniswap V1 交易,从区块 8M 到 9M 实现 98.15 ETH 的收益。根据我们的数据,我们估计只有 63.30%(62.13 ETH)的可用可提取价值被提取。

|

| 秦等人 图 5 |

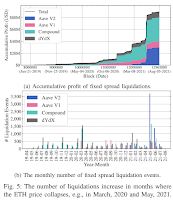

请注意,32% 的非公开三明治攻击产生了 46% 的 MEV,因此将它们保密是有优势的。显然,只有 63% 的潜在 MEV 得以实现,因此还有优化三明治交易策略的空间。关于清算,他们审查了:

从开始到区块 12965000(2021 年 8 月 5 日),Aave(版本 1 和 2)、Compound 和 dYdX 上的所有清算事件。我们观察到总共 31,057 次清算,在 28 个月内产生了 8918 万美元的集体利润(参见图 5a 和 5b)。请注意,我们使用清算平台的价格预言提供的价格在清算时将利润转换为美元。

…

我们在 31,057 起清算事件中确定了 1,956 起交易 (6.3%) 的 gas 价格为零,这意味着清算人在不使用 P2P 网络的情况下私下将清算交易转给矿工。这些私下中继的交易产生了 1069 万美元的总利润。

6.3% 的私人交易产生了 12% 的 MEV。至于套利,他们写道:

从 2018 年 12 月 1 日到 2021 年 8 月 5 日,我们确定了 6,753 个用户地址和 2,016 个智能合约,在 Uniswap V1/V2/V3、Sushiswap、Curve、Swerve、1inch 和 Bancor 上执行 1,151,448 次套利交易,总计总利润 277.02M 美元。我们发现 110,026 笔套利交易 (9.6%) 私下转给矿工,代表提取价值 8275 万美元。

…

ETH、USDC、USDT 和 DAI 参与了检测到的 99.91% 的套利。

请注意,9.6% 的非公开交易占 MEV 的 30%,因此将套利交易保密的优势是显而易见的。 They also investigated attacks that congest the blockchain:

A clogging attack is, therefore, a malicious attempt to consume block space to prevent the timely inclusion of other transactions. To perform a clogging attack, the adversary needs to find an opportunity (eg, a liquidation, gambling, etc.) which does not immediately allow to extract monetary value. The adversary then broadcasts transactions with high fees and computational usage to congest the pending transaction queue. Clogging attacks on Ethereum can be successful because 79% of the miners order transactions according to the gas price

…

We identify 333 clogging periods from block 6803256 to 12965000 , where 10 user addresses and 75 smart contracts are involved … While the longest clogging period lasts for 5 minutes (24 blocks), most of the clogging periods (83.18%) account for less than 2 minutes (10 blocks).

Much longer clogging attacks have happened:

This is what appears to have happened with the infamous Fomo3D game, where an adversary realized a profit of 10,469 ETH by conducting a clogging attack over 66 consecutive blocks.

Blockchain scalability and the fragmentation of crypto by Frederic Boissay et al shows that my Fixed Supply, Variable Demand was correct in suggesting that congestion was necessary to the stability of blockchains. Boissay et al write :

To maintain a system of decentralised consensus on a blockchain, self-interested validators need to be rewarded for recording transactions. Achieving sufficiently high rewards requires the maximum number of transactions per block to be limited. As transactions near this limit, congestion increases the cost of transactions exponentially. While congestion and the associated high fees are needed to incentivise validators, users are induced to seek out alternative chains. This leads to a system of parallel blockchains that cannot harness network effects, raising concerns about the governance and safety of the entire system.

Thus these systems are necessarily vulnerable to clogging attacks.

Capponi et al (11 th February 2022)

In The Evolution of Blockchain: from Lit to Dark , Agostino Capponi, Ruizhe Jia and Ye Wang describe a model built to:

study the economic incentives behind the adoption of blockchain dark venues, where users’ transactions are observable only by miners on these venues. We show that miners may not fully adopt dark venues to preserve rents extracted from arbitrageurs, hence creating execution risk for users. The dark venue neither eliminates frontrunning risk nor reduces transaction costs. It strictly increases payoff of miners, weakly increases payoff of users, and weakly reduces arbitrageurs’ profits. We provide empirical support for our main implications, and show that they are economically significant. A 1% increase in the probability of being frontrun raises users’ adoption rate of the dark venue by 0.6%. Arbitrageurs’ cost-to-revenue ratio increases by a third with a dark venue.

In other words, dark pools transfer MEV mostly from external arbitrageurs to miners, with a smaller transfer to users. But the equilibrium involves continued use of the public mempool because miners enjoy the extra fees arbitrageurs use to attempt to position their trades relative to their victim’s trades. Capponi et al describe a pair of tradeoffs. First, for blockchain users:

On the one hand, using the dark venue alone presents execution risk to users. Transaction submitted to the dark venue face the risk of not being observed by the miner updating the blockchain, who may not have adopted the dark venue. On the other hand, users who only submit through the dark venue avoid the risk of being frontrun.

Second, for arbitrageurs:

Arbitrageurs who only use the dark venue would not leak out information about the identified opportunity to their competitors. They also gain prioritized execution for their orders because miners on the dark venue prioritize transactions sent through such venue. … If instead the execution risk is high, arbitrageurs will use both the lit and the dark venue: through the dark venue they gain prioritized execution, and through the lit venue they are guaranteed execution.

Their model predicts that:

both arbitrageurs and the frontrunnable user will submit their transactions through the dark venue, if sufficiently many miners adopt it.

There is a weakness in their model hiding behind “sufficiently many miners”. Their model of mining consists of:

a continuum of homogeneous, rational miners. All miners have the same probability of earning the right to append a new block to the blockchain.

But this does not model the real world. Miners are not the ones who chose transactions from the lit or dark pools, the choice is made by mining pools , and a small number of large pools have a much higher “probability of earning the right to append a new block to the blockchain”. Thus the use of the dark venue depends upon whether the large mining pools adopt it. Given that typically 2 or 3 pools dominate Ethereum mining, if they adopt the dark pools usage will be high and users of the lit venue will be disadvantaged.

The authors also study dark pool usage empirically:

Our dataset contain dark venue transaction-level data of Ethereum blockchain collected from Flashbots API, Ethereum block data, and transaction-level data from Uniswap V2 and Sushiswap AMMs. Our empirical analysis confirms that the dark venue is partially adopted, and further estimates the dark venue adoption rate around 60% as of Jul 2021. Our analysis also shows that miners who join the dark venue have higher revenue than those who stay on the lit venue.

The methodology described in Seciton 6.3 suggests that what the authors mean is that about 60% of the hash rate has adopted the dark pools; for Ethereum this would be no more than 4 mining pools.

Elder (10 th June 2022)

Bryce Elder’s How should we police the trader bots? is about bots trading in the conventional markets, but the message should be heeded by the developers of cryptocurrency trading bots:

An overarching rule of securities legislation is that market abuse is market abuse, irrespective of whether it’s committed by a human or machine. What matters is behaviour. An individual or firm can expect trouble if they threaten to undermine market integrity, destabilise an order book, send a misleading signal, or commit myriad other loosely defined infractions . The mechanism is largely irrelevant.

And importantly, an algorithm that misbehaves when pitted against another firm’s manipulative or borked trading strategy is also committing market abuse. Acting dumb under pressure is no more of an alibi for a robot than it is for a human.

For that reason, trading bots need to be tested before deployment. Firms must ensure not only that they will work in all weathers, but also that they won’t be bilked by fat finger errors or popular attack strategies such as momentum ignition . The intention here is to protect against cascading failures such as the “ hot potato ” effect that contributed to the 2010 flash crash , where algos didn’t recognise a liquidity shortage because they were trading rapidly between themselves.

Mifid II (in force from 2018 ) applies a very broad Voight-Kampff test . Investment companies using European venues are obliged to ensure that any algorithm won’t contribute to disorder and will keep working effectively “in stressed market conditions”. The burden of policing falls partly on exchanges , which should be asking members to certify before every deployment or upgrade that bots are fully tested in “ real market conditions ”.

It is easy to mandate testing but not so easy to do it. Running the bot against market history is easy but doesn’t actually prove anything because the history of trades doesn’t reflect the effect on prices of the bot’s trades, and thus doesn’t reflect the response of all the other bots to this bots trades, and their effects on prices, which would have caused both this bot and all the other bots to respond, which …

And, even if realistic testing were possible, since the DEX are “decentralized” they have no way to require that bots using them are tested, or how they are tested. So, based on the history of conventional markets, even if cryptocurrencies were not infested with pump-and-dump schemes , flash crashes and the resulting market disruptions are inevitable.

Auer et al (16 th June 2022)

|

| Auer et al Graph 1 |

Raphael Auer, Jon Frost and Jose Maria Vidal Pastor’s Miners as intermediaries: extractable value and market manipulation in crypto and DeFi provides a readable overview of MEV:

Far from being “trustless”, cryptocurrencies and decentralised finance (DeFi) rely on intermediaries who must be incentivised to maintain the ledger of transactions. Yet each of the validators or “miners” updating the blockchain can determine which transactions are executed and when, thus affecting market prices and opening the door to front-running and other forms of market manipulation.

Auer et al explain :

MEV can hence resemble illegal front-running by brokers in traditional markets: if a miner observes a large pending transaction in the mempool that will substantially move market prices, it can add a corresponding buy or sell transaction just before this large transaction, thereby profiting from the price change (at the expense of other market participants). Miners can also engage in “back-running” or placing a transaction in a block directly after a user transaction or market-moving event. This could entail buying new tokens just after they are listed, eg in automated strategies from multiple addresses, to manipulate prices. Finally, miners can engage in “sandwich trading”, where they execute trades both before and after a user, thus making profits without having to take on any longer-term position in the underlying assets.

|

| Auer et al Graph 2 |

They estimate the scale of the problem :

Since 2020, total MEV has amounted to an estimated USD 550–650million on just the Ethereum network, according to two recent estimates (Graph 2, left-hand panel). In addition to sandwich attacks, MEV results from liquidation attacks (ie forcing liquidations), replay attacks (cloning and front-running a victim’s trade) and decentralised exchange arbitrage (right-hand panel; online appendix). Notably, these estimates are based on just the largest protocols and are hence likely to be understated. Thus, the amount of MEV captured in the data is only one portion of the total profits that miners can extract from other users.

|

| Source |

Extracting data from this chart and assuming that the $550-650K represents “price” at the time, it appears that over the same period Ethereum miners earned about $27,616K, so MEV represented only about 2.4% additional mining income. This sounds small, but most of the time Proof-of-Work mining is a low-margin business so 2.4% extra income could well be significant. It isn’t clear how much capital is needed to exploit MEV, so 2.4% needs to be decreased by the cost of the required capital.

Of course, this being Ethereum, capturing MEV has been automated :

“Bots” that exploit MEV are now active on different decentralised exchanges. This imposes a fixed cost of mining, encouraging concentration. Solutions such as moving to dark venues, where transactions are only visible to miners, have not so far reduced front-running risk ( Capponi et al (2022) ). The additional fees and unpredictability for users mean an additional form of insider rents in DeFi markets.

And things are only going to get worse :

Looking forward, MEV could intensify. Indeed, in general equilibrium, miners may be forced to engage in MEV to survive. Miners who engage in MEV will on average make higher profits and buy more computing power, and they could thus eventually crowd out miners who do not. Thus, a form of rat race develops from the combination of the competitive and decentralised nature of updating and the fact that every miner can assemble their block any way they want. It has been argued that MEV forms an existential risk to the integrity of the Ethereum ledger ( Daian et al (2019) ; Obadia (2020) ).

原文: https://blog.dshr.org/2022/09/miners-extractable-value.html